No story begins so humbly as that of God’s incarnation.

An engaged girl of probably meager origins and of marriageable age, which two thousand years ago probably meant an early teen, conceives a child, but not with her fiancée. There’s potential for scandal. Her fiancée, not wanting to humiliate her but needing to be “honorable” within his social context, plans to quietly disassociate himself from her. The girl risks disgrace. But into the story is introduced a figure in a dream who assures the girl’s fiancée that he hasn’t been betrayed, that, in fact, his fiancée carries a child of the Holy Spirit, and that she accordingly fulfills an old prophecy—that a young girl would conceive and bear a son, and call him “Emanuel” (Isaiah 7:14, Matthew 1:23).

With the exception of the dream: the story doesn’t sound like a likely setting for the entrance of a person meant to be the hope for all of humanity.

Perhaps our readings this week revolve around precisely that: divine defiance of expectations. Our passage from Isaiah, long interpreted as a prediction of the arrival of Jesus, mentions the child called Immanuel as a coming sign of God: “Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign. Look, the young woman is with child and shall bear a son, and shall name him Immanuel” (Isaiah 7:14).

This sign lacks the grandeur of other signs, those found in eschatological predictions and elsewhere, those which carry with them hints of the miraculous as evidence of holiness. There appears nothing grand or awe-inspiring about a pregnant young woman. But Isaiah also says that this child, who will dine on curds and honey, would grow to “refuse evil and choose good,” even in a period of great political distress (Isaiah 7:15). “Immanuel” would be a person who, with apparently superhuman consistency, would always choose the hard and righteous path.

Ahaz, in Isaiah, didn’t wish to trouble God for even this small sign: he was enjoined to ask of God a great sign, but declares “I will not ask, and I will not put the LORD to the test” (Isaiah 7:12). Isaiah, apparently sympathizing with Ahaz, declares that Israel shouldn’t weary God with demands for evidence of God’s interest; the only sign to be offered is that of the child borne of a child who will grow to be principled beyond expectation. No grandeur; no fireworks; no miracle, really, unless we’re to cynically declare that principled people are so rare as to become equal to miracles.

Our Psalm reading entreats God for grand signs, of precisely the sort which Ahaz avoided asking for. “Let your face shine, so that we may be saved,” it repeatedly asks, and reminds God that, without the visible presence of God, the people have been wont to drink their tears, and consume their sorrows (Psalm 80:19, 7, 5). The promise of a virtuous child borne of a young girl doesn’t seem a measured response either to these complaints, or to the requests they give way to. Yet Isaiah, though familiar with Israel’s tribulations, predicts that the child will be the sign. The whole sign.

Romans imbues Isaiah’s prophecy with certain characteristics which it doesn’t seem to obviously hold, among them the notion that the child will be descended from the line of David, and that he’ll be a powerful figure. We find Paul conflating noble Immanuel with messianic notions which don’t seem inherent to the Isaiah prophecy. We find him turning the child into a majestic figure, the virtuous boy into a prince among men.

How do we want to look at Jesus? We hold that he is our salvation; we catalogue and cherish his many great deeds and lessons as evidence of his greatness. We believe that he is the son of God. And yet we do all of this remembering his humble origins. We view him without needing to place a crown upon his head; he requires no such validation. We remember him without desiring that he should have overturned whole kingdoms; he was great without such temporal victories.

Instead our focus is upon his birth. We turn our eyes to his mother Mary, the otherwise ordinary young girl who we now treat with reverence and longing, because God chose her as God’s own mother. Though a child, she accepted the decree of an angel and became pregnant with a gift of the Holy Spirit, risking almost certain social irruption to do God’s bidding. Loving God, she risked her entire reputation and position. She gave birth to a child of mysterious origins, one who would become the sign of God predicted in Isaiah, one who would eventually offer hope, and salvation, to all of humanity.

Those who still had their eyes to the sky awaiting magnificent signs might have missed the one sign that superseded all others, the sign who was Jesus; looking for conventional grandeur, of the impressive sort which catches the attention of all, they might not have noticed the boy born of a virgin, raised to eschew all evil and exemplify all good, who grew into a person worthy of being called God’s son.

Our readings remind us that humble origins don’t guarantee a humble existence. God showed God’s face to humanity through the person of Jesus—through one guy in one historical place, whose mother seemed an ordinary enough woman of faith, who was raised by a stone smith while his actual paternity remained “unknown.” God chose him as the entry point into our world; he chose a young girl to give him life, and humble disciples to eventually give his teachings life beyond his own death. God armed him with a simple message: that love of our neighbors is at the heart of the law. God made that the compass by which good could be discerned from evil (Isaiah 7:16).

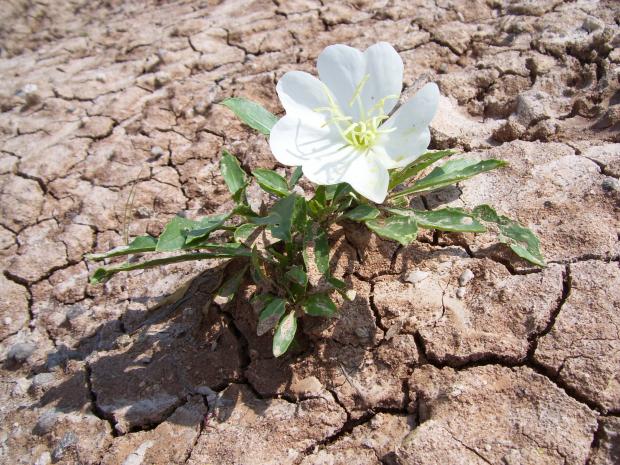

Perhaps we focus upon Mary and the manger in this season to remind ourselves to look for God in unexpected places. Not in palaces or wearing silken roves; not paving our lands with roads of gold and infusing our lives with wealth and comfort. God instead entered our world through a child, and made gifts through him of wisdom and grace. The awesomeness of this was not of an ostentatious sort. The awesomeness of this was that it happened through people who we might think of as “just anyone,” in a time that was essentially “just anytime.” The sign was that God came to us on God’s terms; the suggestion is that it could happen again, anywhere and through almost anyone. God might arrive through any of us. We can look for God everywhere, and find the divine easiest to detect when we stop expecting divinity to come within certain parameters. God knows no limitations and bends to no social conventions.

God is beyond us, but is also in an ordinary young Jerusalem girl, and is in the ear of her concerned fiancée. God’s signs are great, but greatness includes the wonder of an apparently ‘ordinary’ child growing to be compassionate and a healer, a moralizer and a savior. God’s domain remains mysterious and eventual, but it is also always here and everywhere, and God can choose to become apparent through it anytime.

Our readings this week remind us that even the spaces where we forget to look for God are God’s spaces, and that even those people who we forget to think of as God’s are God’s people. God’s own willingness to be humble, shown by God’s becoming like us and loving us always, is the true “miracle” of the Gospels, is the revelation of divinity in an unexpected place. Through the girl Mary we begin to glimpse eternity. Into a stable enters our whole hope.

photo credit here